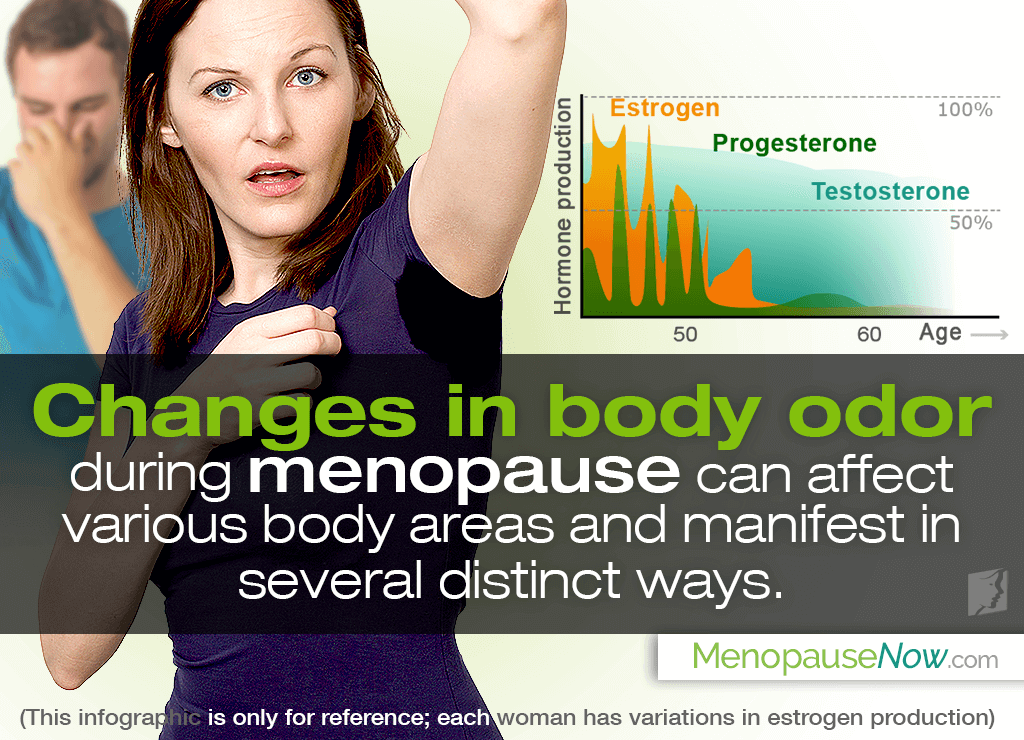

Among the most notorious symptoms of midlife transition are changes in body odor, which can be quite uncomfortable to deal with and even talk about. Most commonly rooted in hormonal imbalance, menopause smells can affect various body areas and manifest in several distinct ways, understandably causing discomfort and embarrassment.

Keep on reading to learn more about four types of body odors during menopause in order to be a step closer to finding proper treatment.

Sweaty Menopause Smells

The most common body odor during menopause is an intensification of the natural scent of sweat. Dipping estrogen levels can trigger many unpleasant symptoms - including hot flashes and night sweats - that can cause excessive sweating as the body tries to cool itself down.1 When the sweat is not absorbed or cleaned away, bacteria will feed on it, producing pungent menopause smells.

Fishy Menopause Smells

Women suffering from trimethylaminuria, a rare condition that causes the body to give off a strong fishy smell, can notice a worsening of symptoms during the menopausal transition.2 While the exact causes of fishy smell during menopause are not well understood, changes in estrogen and progesterone levels are most likely at fault.

It is also worth noting that if the fishy smells originates in the vagina, it might be indicative of an infection that needs treatment.

Fruity Menopause Smells

Another possible cause of menopause smells is diabetic ketoacidosis, which can produce a fruity breath odor. It is a potentially life-threatening complication of diabetes, which occurs when the body does not produce enough insulin and starts break down fat, leading to a build-up of acids in the blood. Diabetic women going through menopause are at a higher risk of complications since hormonal fluctuations may affect their blood sugar levels and how their cells respond to insulin.3

Acidic Menopause Smells

Some middle-aged women also report an acidic, or ammonia-like, urine odor. There are many possible causes of urine smell to become more pronounced, including dehydration, dietary habits, and urinary tract infections (UTIs). Midlife hormonal shifts can affect vaginal flora and increase women's risk of UTIs and urinary incontinence, both of which can make their urine have an ammonia-like odor.4

Conclusions

Because changes in body odor during menopause can affect women's self-esteem, intimacy, and social relationships, understanding their origins is the first step toward healing it. The next step is choosing adequate body odor treatments that focus on restoring hormonal balance in the body, relieving pesky symptoms, and helping women maintain a high quality of life for years to come.

Sources

- Cleveland Clinic. (n.d.). Sweating and Body Odor. Retrieved February 24, 2020 from https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/symptoms/17865-sweating-and-body-odor

- Harvard Health Publishing. (2015). “Not Again!” — When UTIs won't quit at midlife. Retrieved February 24, 2020 from https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/not-again-when-utis-wont-quit-at-midlife-201509258353

- Journal of Midlife Health. (2015). Vaginal pH: A marker for menopause. Retrieved February 24, 2020 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3955044/

Footnotes:

- Journal of Midlife Health. (2019). Menopausal Hot Flashes: A Concise Review. Retrieved February 24, 2020 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6459071/

- National Human Genome Research Institute. (2018). About Trimethylaminuria. Retrieved February 24, 2020 from https://www.genome.gov/Genetic-Disorders/Trimethylaminuria

- Mayo Clinic. (2020). Diabetes and menopause: A twin challenge. Retrieved February 24, 2020 from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/diabetes/in-depth/diabetes/art-20044312

- Korean Journal of Urology. (2011). Urinary Tract Infection in Postmenopausal Women. Retrieved February 24, 2020 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3246510/

- Przeglad Menopauzalny. (2019). Urinary incontinence in postmenopausal women - causes, symptoms, treatment. Retrieved February 24, 2020 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6528037/